Movies

Global-local-global

9/30/20253 min read

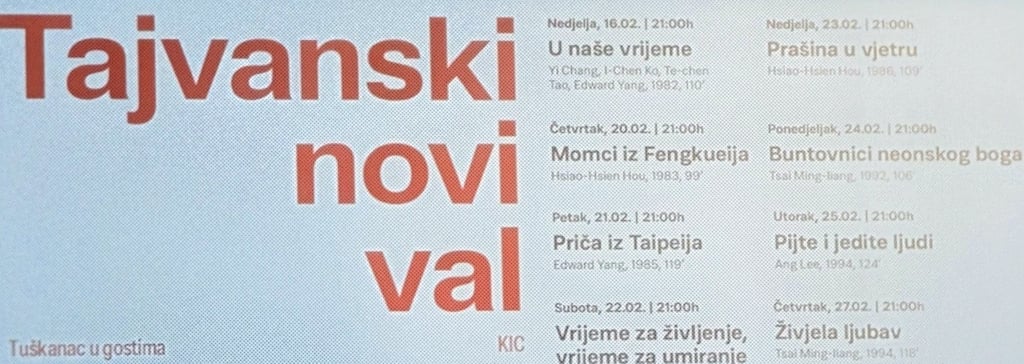

Taiwanese cinema has developed through a Global → Local → Global trajectory.

In the first phase (Global), Hollywood and Japanese cinema (especially after the colonial era) shaped the earliest forms of genre film in Taiwan. Hong Kong cinema — kung-fu and melodramas — became an important model in the 1950s and 60s, while financial and technical models came from the United States and Europe.

The second phase (Local) appeared in the 1980s with Taiwan New Cinema, led by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang. These films told local stories of history, identity, and politics. They used local dialects, family dramas, and often focused on “small” people caught in major historical processes. The aesthetic was defined by a slow rhythm, long takes, and attention to everyday life, while the themes included the colonial past, memory of China, local resistance, and the search for identity.

The third phase (Global again) brought Taiwanese auteurs to the world stage at Cannes, Berlin, and Venice. Taiwanese cinema became a global artistic reference, admired for its poetic rhythm, imagery, and metaphors. Ang Lee built a bridge between Taiwan and Hollywood (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Life of Pi), while Tsai Ming-liang and Hou Hsiao-hsien gained recognition as festival auteurs whose work is now celebrated worldwide.

Taiwan New Cinema – Films as Life Mirrors

🎬 The Sandwich Man (1983, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tseng Chuang-hsiang, Wan Jen)

The film consists of three stories, three directors, and shows the raw reality of ordinary people.

The most famous segment features the figure of the clown, a sandwich-board man advertising in the street. This clown is deeply rooted in the Taiwanese subconscious: a figure that both entertains and provokes pity, symbolizing the transition from poverty to modernization, from comedy to tragedy and back. At this moment Taiwanese cinema began to turn toward realism, local stories, and introspection.

🎬 The Boys from Fengkuei (1983, Hou Hsiao-hsien)

Penghu. Rural life of young men on the edge of delinquency and wandering. The tempo is mesmerizing: slow exteriors, interiors full of interesting compositions. Dialogue is sparse, cold, yet filled with youthful aggression and mischief. Fights are real — clumsy shoving, awkward kicking — nothing like the choreographed grace of Hong Kong kung-fu films. Ironically, the boys watch kung-fu masters in the cinema and dream of being them.

The film shows a harsh reality: cold families, minimal communication, suppressed aggression. Fathers die, life goes on. The only thing sincere is youthful wildness.

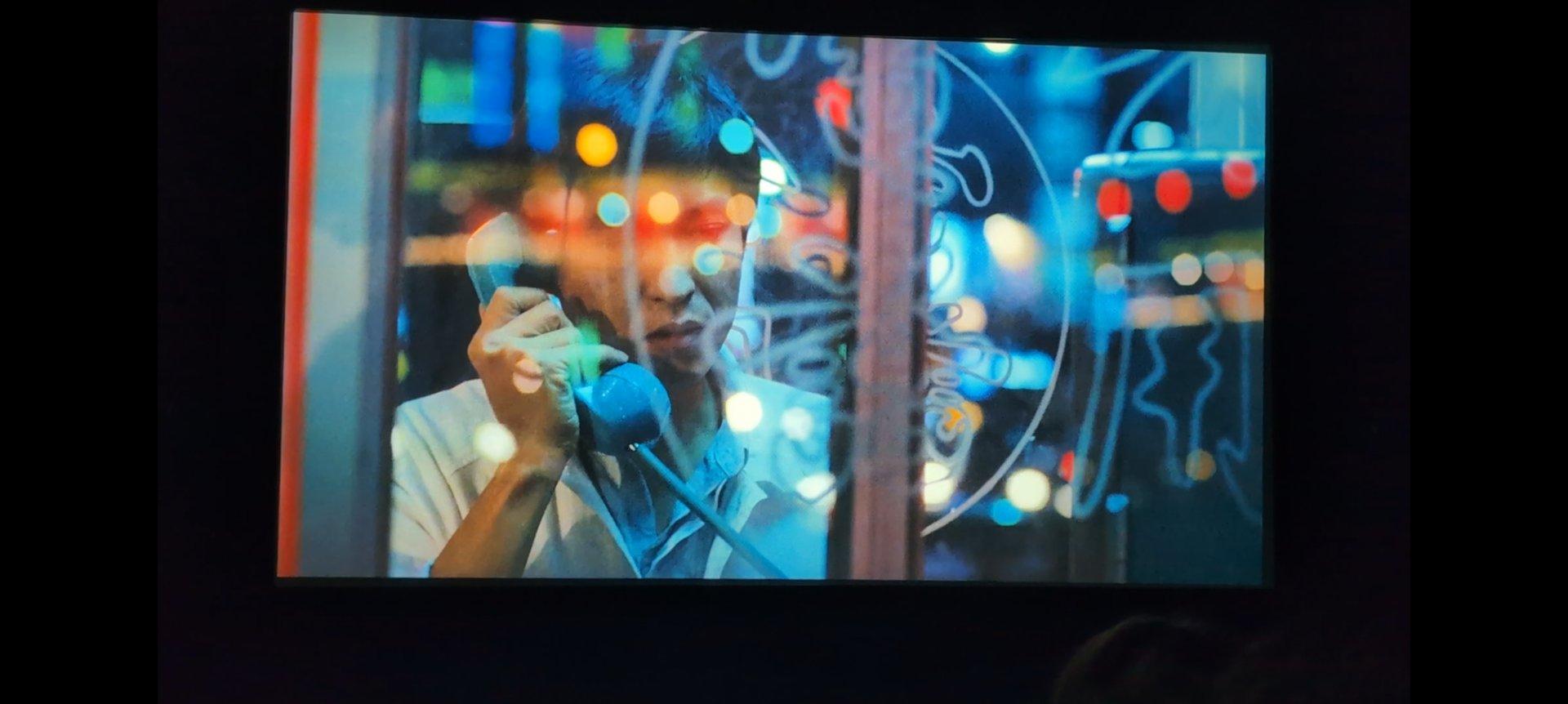

🎬 Taipei Story (1985, Edward Yang)

Unlike the rural Fengkuei, here we are in urban Taipei. The city is cold, marriages fragile: “Marriage and America are not the cure for everything.”

There is a memorable line:

“After the Vietnam War many foreigners left the island, houses were empty, so my parents rented one, then bought it. Now Yangmingshan is elite. We can easily sell it.”

Already in 1985 Yang foresaw that data centers would be the business of the future.

TThe film blends images of corporate Taiwan with four key figures: a taxi driver and his gambling wife, a man living off the shadows of past success, and a woman pushing forward, though empty inside. The lighting is full of contrast; interiors and exteriors tell their own stories. Small details — door handles, switches, kettles — look the same as today.

🎬 Dust in the Wind (1986, Hou Hsiao-hsien)

A film that feels like the memory of a dream. What remains is a warm scene of family and soldiers after a shipwreck. The whole film breathes amnesia and nostalgia.

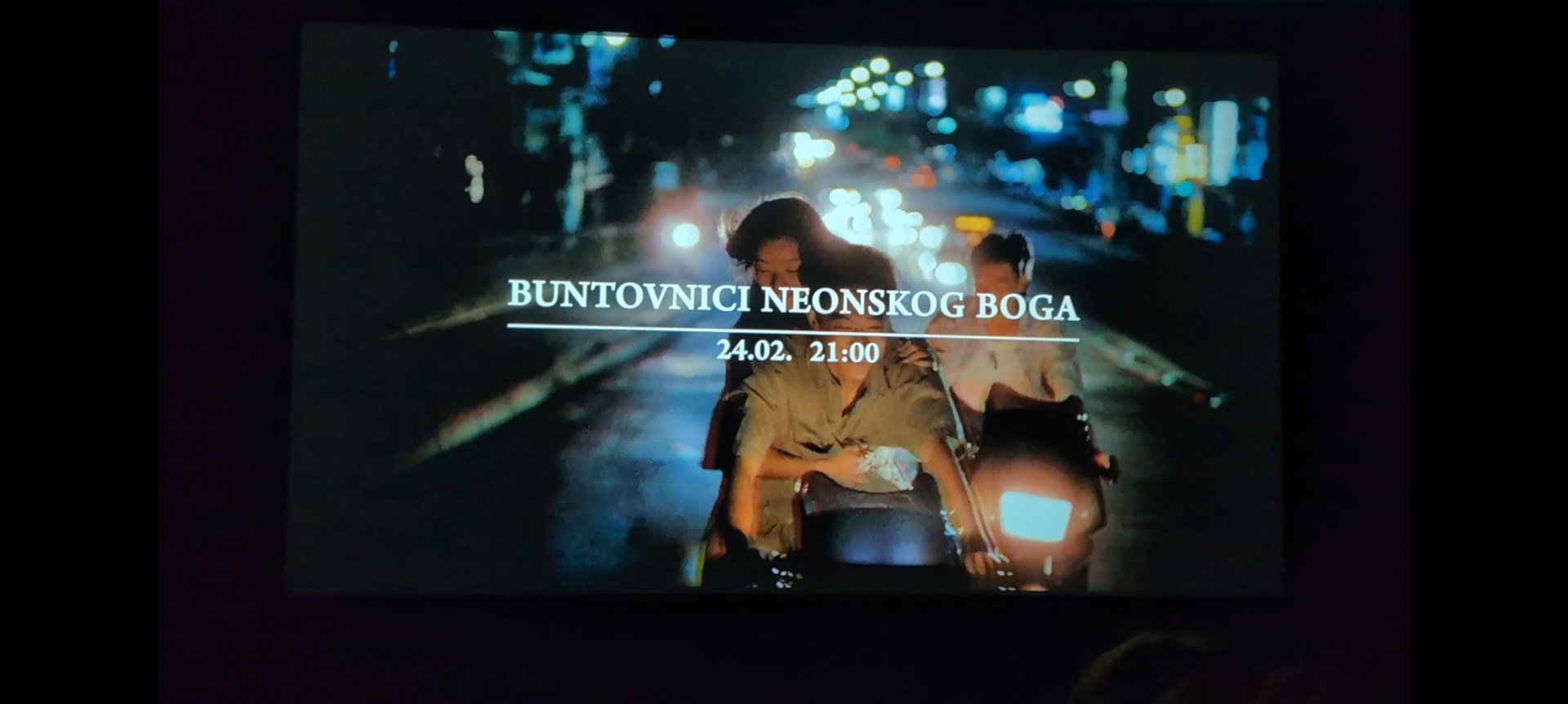

🎬 Rebels of the Neon God (1992, Tsai Ming-liang)

Cold, brutal, alienated. The concrete of Taipei presses down on its characters. Youth without a way out — except perhaps in a gaze lifted toward the sky.

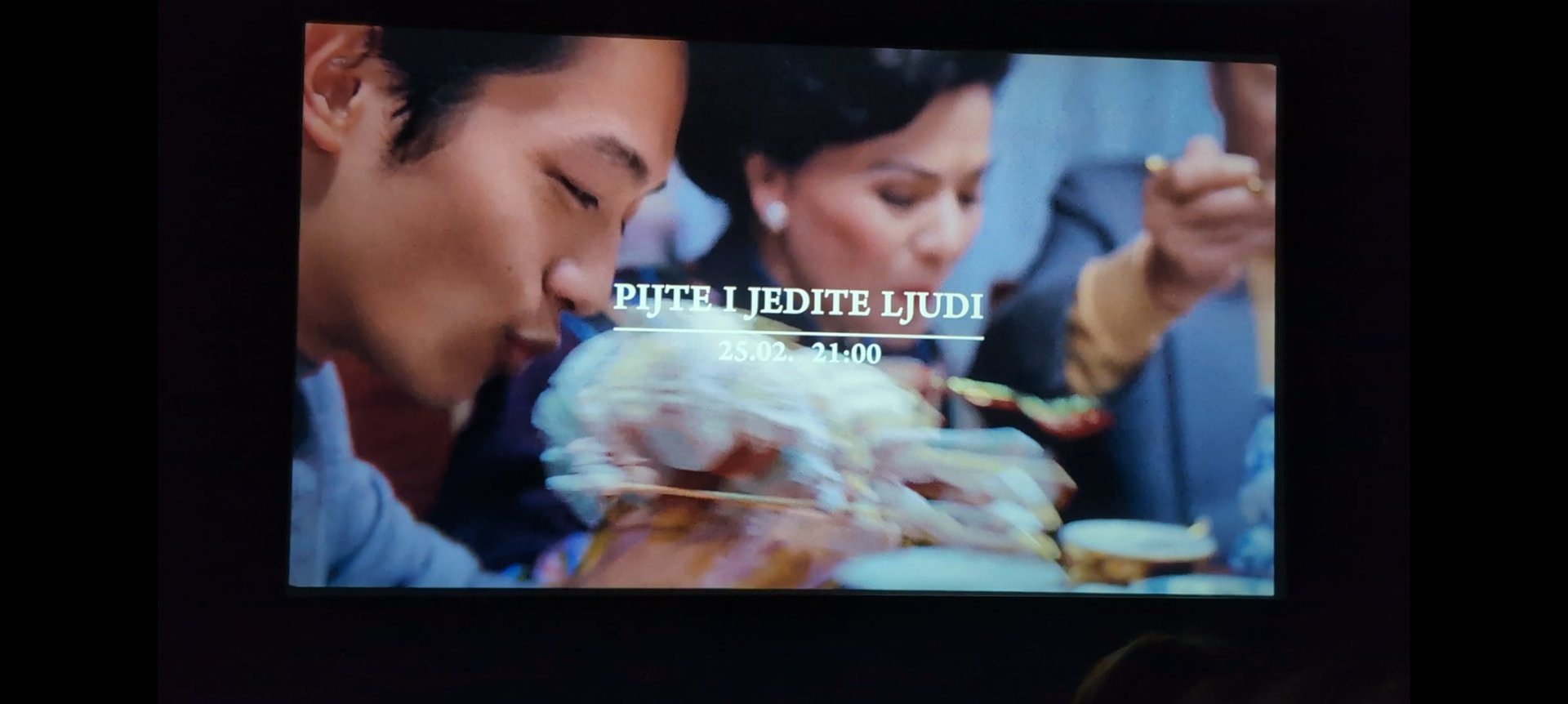

🎬 Eat Drink Man Woman (1994, Ang Lee)

A masterpiece. Full of food, people, lives, temporality. A monolithic work of Taiwanese cinema, where emotions, family, and cuisine intertwine into one great symphony.